Table of Contents

- 1 How Hotel Pricing Works

- 2 Now for a Brief History Lesson

- 3 Variable Pricing Strategies Make Pricing Dynamic

- 4 Sliding under the BAR

- 5 Rise of the Guardians & Revenge of the Nerds

- 6 Introducing The Rule of Reason and the Introduction of Unreasonable Rules

- 7 The UK Doesn’t Just Have Different Rules for Spelling and Driving

- 8 Why the UK Office of Fair Trading (and the European Union) are Getting this All Wrong

- 9 A Reality Check – Why Rate Parity is Beneficial to All Parties

- 10 A World Without Hotel Rate Parity

NB: This is an article written By : Robert Cole the founder of RockCheetah

Hotel rate parity is an incredibly divisive issue, with investigations, litigation and confusion running rampant around the globe. Government officials, class action attorneys, hoteliers and online travel agencies (OTAs) are all engaged in a fight with considerable implications.

Be the first to know, sign up here and stay up to date with our latest revenue management news, updates and special offers

Hotel brands and OTAs rely on rate parity as the basis for consumer best price guarantees. Lawyers call it Resale Price Maintenance (RPM.) The uninformed call it price fixing. Only one thing is for certain – passions run high and everyone feels they are somehow being wronged by the accusations of the other side.

The UK Office of Fair Trading (OFT), the French Competition Authority, the Swiss Competition Commission and Germany’s Federal Cartel Office are all investigating the practice. Some opportunistic US lawyers are busy filing class action suits.

The allegations range from hotels artificially inflating consumer prices, to OTAs using their market power to prohibit hotels from giving competitors lower prices, to hotels colluding with the OTAs to limit the number of competing OTAs.

Oddly, as oppositional and contradictory as these charges may be, they pertain to exactly the same pricing mechanism. It would seem to be highly unlikely that all suppliers and distributors, both severally and collectively, are simultaneously leveraging their market power to constrain trade with each other.

What follows is an attempt to remove the emotion, evaluate the facts, and come to some reasonable conclusions about the nature of hotel rate parity – it is easiest to think of it as a Manufacturers Suggested Retail Price. From here forward, I’ll call it RPM, not only because that’s the correct legal term, but just like automotive engines, when RPM’s get high, there’s often lots of loud whining, uncontrollable shaking, billowing smoke, and the emission of noxious gasses…

How Hotel Pricing Works

Before getting into the details of RPM, it’s beneficial to understand why hotels apply the practice in the first place. It is all based on how hotels have traditionally been priced and sold.

A hotel product is not simply a room. It is actually the combination of 1) a room category (inventory) and 2) a rate plan (price.) This is very similar to an airline, where a comparable product is created by pricing an Economy class seat (inventory) with, for example, a Y (unrestricted,coach) fare.

A hotel room category is normally a variety of rooms or room types that may or may not relate to a grouping of physical room numbers. A room category may be based on the room size, view, building/floor, bedding, room features, amenity package, special services, accessibility, elevator proximity, renovation status, or frankly, anything else the hotel might come up with to efficiently manage its inventory.

Perennial favorite room categories for consumers are “Partial Ocean View King” and “Run of House.” Oceans are big. Partial views sound quite small. One always wonders if such a view requires standing on the patio chair to catch a glimpse of the ocean around the side of the hotel. Run of House simply means there is no specific type of room associated with the rate. However, any particular hotel’s translation for ROH could fall anywhere between “whatever we have left” to “tipping the desk clerk might improve your options…”

Hotel rate plans, on the other hand, define the actual monetary value assigned to each of these types of room. They are more virtual in nature. They might be associated with a specific distribution channel, transaction model, agency relationship, market segment, corporation, group, travel management company, advance purchase timeframe, yield tier, payment method, or again, any other pricing method that might work for the hotel.

But the complexity does not stop there. The length of stay may also influence product availability or pricing (for example, a three night stay may be priced less or offer greater availability than any single night stay during the same timespan. A good example is how LAs Vegas casinos control inventory and pricing over high demand weekend periods, or Dallas hotels manage inventory over Texas-OU weekend. These are called Full Pattern Length of Stay controls. Adding closed to arrival, minimum stay or no departure constraints to seasons or date ranges can add further dimensions to a hotel product line.

Additionally, there may be inventory allocations or rate fences established that close out availability of specific room categories or rate plans at defined occupancy levels, or after a certain number of reservations are booked for a specific category, plan and/or combination. The lead time prior to arrival is also considered when applying such rules.

Just to make certain there are a daunting number of pricing/availability permutations and combinations, floating pricing tiers may be overlaid as an additional dimension.

To make matters worse, since not all rate plans apply to all room categories, the resulting array of options can be anything but intuitive – for consumers and hotel management alike.

Ultimately, this all winds up getting worked out at the property level, where there may be varying degrees of expertise or revenue management system sophistication to coalesce all these options into a logical, consumer friendly strategy. As a result, two similar properties could offer consumers dramatically different pricing structures and discounting strategies for a remarkably similar product offering.

But hotels are not just only sold directly to consumers. Intermediaries, such as OTAs, play a significant role in the hotel distribution equation.

Distribution through third parties doesn’t make things any easier. Intermediaries can sell hotels under two methods – First, is a retail model, where the hotel serves as merchant of record for the sale and an intermediary serves as its agent, receiving a commission in exchange for referring the sale. OTAs often call this the Commission or Agency Model. Booking.com typically sells hotels under the agency model, as do most traditional travel agencies.

The second is a wholesale model, with the intermediary serving as the merchant of record for the sale, marking up a net rate provided by the hotel. The intermediary profit is the difference between the net rate and the retail price charged to the consumer. This is commonly referred to by OTAs as the Merchant Model. It is the predominant method employed by Expedia/Hotels.com and most tour operators for hotel bookings.

But not all merchant model bookings are created equal. A net rate for a wholesaler selling a room-only booking might float at 15% under the hotel’s best available rate, where a wholesale package rate might receive a 25% discount. An opaque rate, used to move distressed inventory through Priceline could see a 50% price reduction.

Unlike consumer package goods, the Manufacturers Suggested Retail Price is not simply $299 for a 32GB iPhone 5s until Apple decides to release it next model. Hotel prices can change instantaneously based on perceived fluctuations in market demand, competitive actions or the number and pricing of reservations on the books – for various stay patterns – for various arrival dates streaming into the future.

There is little fixed when it comes to hotel pricing.

Now for a Brief History Lesson

Given the highly variable nature and extreme complexity of hotel pricing structures, it is important to note that hotel rate parity RPM is nothing new.

The merchant model was born decades ago (unquestionably as early as the 1950’s,) when tour operators contracted hotel rooms at net wholesale rates. Those rates were explicitly made available only for sale in combination with flights within inclusively priced travel packages. The wholesalers (often referred to as consolidators) were free to offer discounted package pricing that was lower than the combined retail prices of the individual travel components.

In some cases, the discounts could be so deep that one of the travel components might appear to be offered free of charge. This was acceptable to the hotels and airlines as it was impossible for consumers to determine the underlying pricing of the individual components.

Room-only hotel sales at these net rates were explicitly forbidden. If the tour operator did offer a standalone hotel product, those rooms could be sold on a commissionable basis, or at higher (lower percentage discount) net rate plan quoted by the hotel, if the wholesaler desired to sell the room naked and maintain its role as merchant of record.

In some cases, hotels might agree to deeper discounts/higher commissions for international guests in consideration of the potential to capture incremental sales and the inability for domestic consumers to learn of special pricing made available solely to those living on another continent. This was especially true if retail distribution was primarily channeled through retail travel agencies.

Over the years, a strict policy was applied to negotiated corporate, preferred travel agency, consortia, group and government rates, as well as for complimentary or bartered room inventory. The policy fundamentally forbid these organizations from the “onward-distribution” of discounted rates to third parties or unaffiliated consumers at rates that undercut the hotel’s retail pricing.

To a large extent, these policies still remain in effect today. it is what keeps every travel agency from quoting a unique rate that is different from the rate quoted by the hotel or any other travel seller on the planet. If such a policy was allowed, consumer confusion would be rampant, with the introduction of tremendous market inefficiency surrounding a low price search process.

Variable Pricing Strategies Make Pricing Dynamic

One change from the distant past was the advancement of technology that allowed pricing to be instantly changed at the discretion of the hotel. Earlier, hotels would commonly negotiate tour operator and corporate rates on an annual basis, often in the summer preceding the year to be contracted. This resulted in static rates extending out 15+ months that could leave the hotel uncompetitive if they overestimated demand, or leave money on the table if demand was underestimated.

Worse yet, if hotels adjusted their retail pricing based on updated demand forecasts at some point throughout the year, previously contracted tour operator margins could get squeezed if prices were reduced, or wildly inflated if retail pricing was raised.

Fortunately, once travel agencies, OTAs, corporations and tour operators were able to electronically interface with hotel reservation systems to interactively transmit rate and availability queries, new relative pricing structures were developed. Discounted and wholesale rate plans could then be priced at a percentage off of the BAR (Best Available Rate,) or the lowest generally available, published rate for a particular stay pattern.

The whole pricing structure may also be pegged to vary based on increases/decreases in the BAR. One large hotel group allows up to 28 rate tiers so relative pricing schemes may be ratcheted up or down depending on forecast demand.

The greatest benefit of this approach was the ability to unify the strategies governing property retail pricing structures with intermediary agency and merchant model compensation models.

If a hotel charged $200/night, an OTA receiving a 20% commission would receive $40 under the agency model and an OTA receiving a 20% discount under the merchant model would see a $160 net rate – yielding a $40 margin on the sale.

The benefit not only reduced market confusion by presenting clear consumer messaging regarding pricing across hotel-direct or intermediary channels, but it also enabled hotels and OTAs alike to offer best rate guarantees to consumers, confirming the integrity of their branding.

If the hotel later dropped the BAR to $180, the agency-model OTA commission would automatically be reduced to $36.00, matching a new OTA merchant-model margin of $36.00 on an adjusted $154.00 net rate.

In each case, consumers reserving a standalone hotel room would receive the lowest publicly available rate, regardless of the booking channel or business model it was purchased under.

This is where uninformed accusations of “price fixing” fall apart. Hotels independently set prices based on market conditions, not under the collusion-inspired duress wrought by competitive hotels and/or intermediaries, as imagined by delusional conspiracy theorists. RPM is used to effectively manage the frequent price variations across multiple business models and distribution channels for a perishable product.

The practice enables the added consumer protection of the best price guarantee.

Sliding under the BAR

But hotels don’t sell all their product under direct, agency or merchant rate plans that operate under RPM. Three additional online distribution products are available to quote rates for sale that are not subject to RPM: Opaque, Package & Private Sale.

Opaque covers Priceline’s reverse auction “Name Your Own Price” model, as well as their new “Express Deals” option that mimics Hotwire’s opaque hotel product where the rate is revealed, but not the property name until after the purchase is consummated. Brand agnostic consumers can normally save 20-50+% by waiting for the hotel to be revealed after the booking. To see how to game the opaque sites for fun & savings, see Travel Gamification – How to Save Money Booking Hotels.

The standard opaque pitch is that these sites make a pool of brand-agnostic consumers available to hoteliers who then have the opportunity to wow the guest with service and convert them to repeat guests. Two flaws in this logic are apparent – First, these consumers are already brand indifferent, with that behavior reinforced with up to 70% savings as a reward. Their loyalty aligns with the discounted booking channel, not the hotels that it assigns them.

Secondly, it is a fairly tall order to win over a new client, not because the hotel stay isn’t great, but when the price is doubled for a return trip, a completely different value paradigm exists. For guests already comfortable booking opaque hotels, why should they take the risk of staying at a known property at little or no discount when maybe an even better hotel is available at a lower price? Like the roulette wheel in Las Vegas, the game is specifically designed to tip the odds in favor of the house – in this case, the opaque travel site.

Hailing back to its wholesale roots, hotels are still generally sold below retail pricing within multi-component packages. With the advent of dynamic packaging, it is now relatively common for a traveler to create their own custom packages by combining a car rental or flight booking with a hotel stay to capture a discount.

The savings are typically sourced from the hotel discounts. Some OTAs do a poor job of combining car rental, treating it as a transparently priced add-on, which largely eliminates the ability to bundle in car rental discounts as well.

Proponents of dynamic packaging tout its superiority to opaque models for distributing discounted hotel rates and distressed inventory. Booking a hotel on an opaque website may shield the hotel brand prior to the sale, but once transacted, the guest knows the exact price for the hotel.

Because the relative wholesale pricing of the travel components is not known, and inventory may be sourced across multiple pricing tiers, hotel retail pricing integrity is maintained. It is difficult for travelers to reliably discern the underlying hotel pricing within a package. As a result, there is no practical need for resale price maintenance on package sales.

Private Sale websites are largely a misnomer. Members may see rates lower than BAR pricing, value added benefits, or sometimes both. The one stipulation is that the user must be registered for the service, so the rates are hypothetically suppressed from public view on a password protected site.

In most cases however, the websites require little more than an email address or registration via Facebook Connect to join their member communities. No fees or other qualification criteria exist – all are welcome. While this degree of inclusiveness is admirable, the composition of the membership is largely indistinguishable from the general public.. The bar established to vette suitability for membership is set unfathomably low – if bar exists at all.

Rise of the Guardians & Revenge of the Nerds

Hotel Reservations Network (HRN), the predecessor of Hotels.com, emerged early in the pre-internet 1990’s as a modern consolidator that focused on standalone hotel bookings. Agreements were simple and intentionally signed at property level in order to avoid interference from brand corporate offices. As HRN grew, hotels largely failed to recognize the ramifications of offering low wholesale rates without requiring prepayment or sharing inventory risk.

Unencumbered by restrictive contractual terms, HRN gained experience selling across multiple brands and a growing selection of geographic markets. With the advent of the internet, HRN leveraged its superior (although still rudimentary) business intelligence to offer consumers a best rate guarantee.

During peak demand periods, when HRN was inclined to optimize its margins, they often offered pricing higher than hotel-direct pricing. Few guests were inclined to test the veracity of the low price guarantee. During need periods, however, HRN aggressively under-cut hotel pricing to shift share and drive volume.

HRN smartly positioned itself to support do-it-yourself hotel booking through improved price transparency and comparison shopping. By 2001, many hotel groups intervened to negotiate more favorable terms on behalf of member hotels – normally introducing RPM conditions to regain some control over retail pricing.

The terrorist attacks of 9/11/2001 again altered the playing field. OTAs capable of channelling demand to desperate properties were openly allowed to violate RPM terms by desperate hotel managers. For a distressed hotel with ample room inventory, any booking was better than an empty room that had no prospect for sale through any other channel – regardless of a hotel brand’s recommendation to resist such temptation.

In 2004, the InterContinental Hotels Group (IHG) distribution agreement was up for renewal. Expedia presumably sensed an opening to be opportunistic – As IHG only managed 200 of their 3,000+ properties, one could imagine it would be difficult to control franchisees who reportedly received upward of 15% of their transient business through Expedia’s websites that now included Hotwire and HRN, renamed as Hotels.com.

Expedia reportedly went all-in; demanding last room availability and the elimination of rate parity conditions. Expedia apparently guessed wrong.

IHG managed to convince its franchisees that they would forever lose control over their retail pricing structure if they acquiesced to Expedia’s demands. Instead of breaking the back of a major hotel group, with the potential for others to fall like dominoes based on this precedent, IHG stood firm and terminated its Expedia agreement. This single event emboldened other hotel groups that had been lackadaisically managing OTA RPM to start aggressively monitoring compliance and tighten contractual terms.

However, when the global financial crisis hit in 2008, many amnesiac hoteliers, forgetting their post 9/11 travails, again permitted the widespread undercutting of rates. This was sometimes exacerbated by the elimination of corporate positions responsible for monitoring compliance due to budget cuts.

At the present time, most major hotel groups and independent properties with competent revenue management capabilities operate with a low price guarantee pegged to the BAR and unilaterally apply RPM across all their room-only agency and merchant distribution channels.

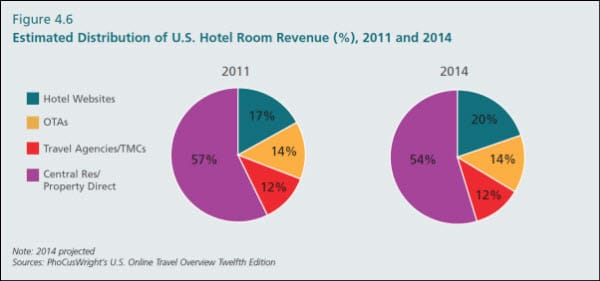

Again the spurious price-fixing allegations also ignore the reality that only about one-third of hotel revenue is sourced through online channels. PhoCusWright’s Online Travel Overview, Twelfth Edition projects OTAs to generate 14% of US hotel revenue in 2014 – the same ratio as in 2011. That does not reflect a marketplace with OTAs exerting undue control over hoteliers.

PhoCusWright’s research projects more hotel room revenue sourced from hotel websites, but the gains are from offline hotel direct channels.

Similarly, the forecast growth of hotel website-sourced revenue share is not the result of fictionalized collusion by hoteliers wreaking revenge on OTAs, but the understandable shift from offline hotel direct and central reservations traffic to the hotel websites. Hotel corporate and group business segments continue to drive considerable volumes of business – largely outside the control of the major OTAs.

Given that the maturity of the US hotel market relative to online hotel booking predates markets within Europe and Asia Pacific regions, the US should provide an excellent example of a marketplace flourishing with ubiquitous RPM practices. Consumers are not disadvantaged. Neither hoteliers nor intermediaries are restraining trade or driving the other from the market due to iron-fisted control over distribution channels.

Introducing The Rule of Reason and the Introduction of Unreasonable Rules

With a mature market like the US functioning well, what could possibly be the problem? There is one legal twist – globally, legislation governing Resale Price Maintenance varies dramatically between jurisdictions.

The United States Supreme Court ruled in Leegin Creative Leather Products, Inc. v. PSKS, Inc. that vertical price restraints are to be evaluated based on the Rule of Reason. The rule distinguishes between price restraints with anti-competitive effects that are harmful to consumers, and those with procompetitive effects that are in the best interest of consumers.

When fundamentally weighing the benefits against the harm, the foremost issue is evidence of consumer injury as a direct result of the practice. There is no evidence of consumers being disadvantaged by rate parity policies with hotels; it is therefore permitted.

A major concern about RPM is it enables a practice that facilitates retailer and supplier collusion, for example, the exclusion of more efficient retailers by a supplier. This is not the case with hotels. Under the agency model, a more efficient travel retailer operates more profitably than its respective competitors. Under the merchant model, a more efficient wholesaler is able to derive the same profitability as a competitor at a lower degree of discounting by the hotelier. In the cases above, markets operate smoothly pursuant to capitalist principals.

A good example of an industry where RPM could have a detrimental impact on consumers would be pharmaceuticals, due to the proprietary nature of drugs and a lack of alternatives for an inventoriable product where prices rise when supply is artificially constrained. Hotels are largely a commoditized, perishable product that loses revenue if the supplier chooses to artificially constrain supply.

Even for merchant model transactions, the OTA is not a reseller in the classical sense. OTAs rarely incur any form of inventory risk through block commitments or prepayment. In most cases, even when the traveler prepays for the hotel room under a merchant transaction, the hotel is not paid until after the guest departs. Traditional reseller models have the reseller purchasing the goods from the supplier, incurring full inventory risk and then needing to sell the product on a retail basis to recoup their outlays. Under this scenario, it is important for the reseller to be able to reduce pricing as market demand decreases in order to effect a sale.

Competition-related challenges may also arise when consumers do not have access to low price discount alternatives. This is certainly not the case with hotels as opaque websites almost always offer discounted rates well below those offered on a retail basis. Also due to market forces and the fragmentation of the hotel industry, a large number of comparable hotels typically exist within any specific geographic area. Access to alternative and/or discounted product is not a common problem for travelers.

The UK Doesn’t Just Have Different Rules for Spelling and Driving

In the United Kingdom, the 1964 Resale Prices Act deemed all resale price agreements to be against the public interest, unless proven otherwise (pretty much the inverse of the 2007 US law.)

The issue of hotel parity was never raised until 2010 when Skoosh, an insignificant OTA with a hypothetical business model predicated on disregarding hotel contractual terms that required RPM, made reckless accusations of price fixing a) between hotel brands, 2) between OTAs and c) between hotels and OTAs.

The laughably ill-informed and naive accusations included rampant confusion between agency and reseller roles, resale price maintenance and most favored nations agreements, and the fundamental process of how hotel rates are established (which is incidentally, independently and at the property level.)

It was difficult to imagine how such wild fictions could be taken seriously, however the one organization that understood hotel distribution less than Skoosh was the OFT. And so, the boondoggle began.

After a two year investigation, the OFT alleged that Booking.com and Expedia each entered into separate agreements with InterContinental Hotels Group that restricted each OTA’s ability to discount the rate at which room only hotel accommodation bookings are offered to consumers. Because RPM is per se illegal by law in the UK, the OFT felt compelled to act.

The decision specifically cited a violation of Article 101(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, which states:

Article 101

1. The following shall be prohibited as incompatible with the internal market: all agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices which may affect trade between Member States and which have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition within the internal market, and in particular those which:

(a) directly or indirectly fix purchase or selling prices or any other trading conditions;

(b) limit or control production, markets, technical development, or investment;

(c) share markets or sources of supply;

(d) apply dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions with other trading parties, thereby placing them at a competitive disadvantage;

(e) make the conclusion of contracts subject to acceptance by the other parties of supplementary obligations which, by their nature or according to commercial usage, have no connection with the subject of such contracts.

Any reasonable person reading that passage would naturally conclude that any violation would produce evidence that the actions of the transgressors “have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition.”

However, the OFT decided to take a remarkably creative approach to interpreting the law by explicitly stating in Section 4.3 (The OFT’S Competition Concerns) of its document rather circuitously titled “Hotel online booking: Notice of intention to accept binding commitments to remove certain discounting restrictions for Online Travel Agents”:

The OFT considered that it was not necessary to demonstrate that the Relevant Price Agreements did, in fact, have anti-competitive effects in order to establish an infringement of the Chapter I prohibition and Article 101(1) TFEU

One would think that after investigating business practices in concerning the Competition Act and cartels (which is how this content is categorized on the OFT website), the OFT would be hell-bent on proving legal infringements by exposing a conspiracy among hoteliers or OTAs. One can only conclude that after two years of investigation, insufficient evidence of collusion or conspiracy existed – largely because it never occurred.

This thesis is supported by the actions of the OFT itself. Instead of arriving at a decision and enforcing the TFEU statute, the OFT appears to have admittedly confessed that it has not arrived at a decision, and instead has adopted the tangential strategy of securing commitments from the parties subject to Section 31A of the Competition Act of 1998.

The pertinent section states:

31A. Commitments

(1) Subsection (2) applies in a case where the OFT has begun an investigation under section 25 but has not made a decision (within the meaning given by section 31(2)).

(2) For the purposes of addressing the competition concerns it has identified, the OFT may accept from such person (or persons) concerned as it considers appropriate commitments to take such action (or refrain from taking such action) as it considers appropriate.

As a result, a truly bizarre resolution was adopted cooperatively by the OFT, Expedia, Booking.com and InterContinental Hotels Group. Full documentation can be found at the OFT Website: Investigation into the hotel online booking sector

To summarize, the following commitments would be made for a period of at least three years:

- The Commitments concern the freedom to offer Reductions in respect of Hotel Rooms at Hotel Properties located in the EU by OTAs to Closed Group Members who are UK Residents and who have made at least one Prior Booking with that OTA.

- The freedom to offer Reductions will be given to OTAs operating under any business model, irrespective of, for example, whether the Closed Group Member pays for the hotel room booking at the end of the hotel room reservation process or after his or her stay at the relevant hotel, or to whom the Closed Group Member makes payment.

- IHG will clarify or amend any existing commercial arrangements, if necessary, with Other OTAs to ensure that these arrangements comply with the Principles without undue delay… [and] ensure that, for the duration of the Commitments, any new commercial arrangements with Other OTAs comply with the Principles

- Reductions may be no greater than the level of commission earned by that OTA for the relevant Hotel Property.

- OTAs may publicise information regarding the availability of Reductions in a clear and transparent manner, including to price comparison websites and meta-search sites [but] cannot publicise information… which would allow a discounted retail rate to be calculated to consumers who are not Closed Group Members.

- Reductions means reductions off Headline Room Rates, for example by way of discounts, vouchers, rewards and/or cash back…

- Closed Group means a group where membership is not automatic and where: (i) consumers actively opt in to become a member; (ii) any online or mobile interface used by Closed Group Members is password protected; and (iii) Closed Group Members have completed a Customer Profile.

Breaking this down, the OFT managed to strike a dubious Trifecta of a) Not helping consumers that have never booked through an online travel agency, b) Merely redefined an OTA as a Private Sale website and c) Undermining the retail pricing structure of the hotel industry.

The burning question is why would the companies involved not just tell the OFT to pound sand and come back when they had firm evidence of anticompetitive behavior and damage inflicted upon markets or consumers.

Based on pure conjecture, there would be no incentive to fight such a decision if it was beneficial to the organization. For Expedia, this commitment creates an outcome that fulfills fifteen years fighting to establish a competitive advantage under the merchant model by setting prices a levels below those offered by the hotel. Booking.com, as an agency model shop, would be equally thrilled by the structure of the commitments that provide them with similar advantages.

As far as IHG is concerned, it is hard to say why they failed to put up a fight. The burden of proof would have been on them to prove that hotel rate parity clauses do not “effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition,” but it appears that the OFT had a hard time proving that they do… At the least, they could have started with the points I raised above.

I am desperately hoping that they were not trying to be clever, egotistically believing that while the elimination of rate parity would suck for the hotel industry, it would suck less for them, given their global footprint and asset-light portfolio. When revenue streams are reduced, hotel owners get squeezed because they bear the operating costs and debt service; the brands continue to collect to be compensated for their franchise fees, albeit adjusted for lower hotel revenues.

Somewhat tragically, as much of a beneficial service that was done for the hotel industry by IHG’s management team in 2004, an equally, if not more disastrous degree of damage will be inflicted upon the industry when these conditions are adopted by the EU – which appears likely given the defined scope of geographic market coverage detailed in the commitments.

There will also be intense pressure for the elimination of resale price maintenance in other jurisdictions – regardless of standing legal precedent. Remember that old HRN divide & conquer strategy? Get ready for it to be deployed by market managers on a newly enriched, weaponized level.

But before predicting the impact on the hotel industry, let’s first cover why this ill-advised decision by the OFT lacks merit.

Why the UK Office of Fair Trading (and the European Union) are Getting this All Wrong

Resale Price Maintenance, as manifested by the global hotel industry, is procompetitive and in the best interest of consumers.

The points below highlight the principal arguments that RPM should be outlawed due to a negative impact on consumers. Clearly, none of these scenarios apply to hotel RPM policies.

Hotel RPM practices are not anticompetitive, because they do not:

- Eliminate retail price competition between brands that independently establish Resale Price Maintenance

- Reduce intrabrand competition. (Many distribution alternatives exist for any single hotel property)

- Set absolute pricing on a brand level. (Absolute hotel prices are set at the unit level – especially because most are independently owned, managed and/or branded)

- Establish a fixed or minimum retail price. (Nearly universally, hotels are variably priced; RPM only applies at each hotel’s absolute price level before it is changed based on market conditions)

- Enable promotion that exploits consumer information gaps through misleading or fraudulent retail sellers

- Facilitate cartel conduct at the supplier or retailer level

- Threaten efficient or innovative retailing

Additionally, RPM does not reduce competition among hotels or Online Travel Agents for the following reasons:

- If an OTA has market power, it can be exerted through wholesale pricing discounts or most favored nations agreements, not resale price maintenance

- Hoteliers have no incentive to discourage competition among retailers. (History shows retailer cartels sell less than competitive retailers, so Hoteliers are worse off if retailers form a cartel)

- It keeps discounting retailers from riding free on other retailers presale services

- Typically, when brands are strong, gross selling margins of suppliers tend to be high and retailer margins tend to be small. (This is not the case with hotels (during the economic downturn, OTAs had record hotel profits while hotels had record losses)

- No evidence that Resale Price Maintenance for hotels reduces total product sales

- The hotel industry is not dominated by brand selling. While Brands sell aggressively through national and regional sales offices, selling remains largely distributed at the property level.

- Hotel unit or brand market share does not exceed 15% (a level the European Commission uses as a standard.) While not directly relevant, RPM terms are stricter in Europe than the US)

- Even under the merchant model, OTA/Hotel relationships are largely agency relationships with the OTA incurring limited selling risk. (OTAs normally do not take inventory risk on stand-alone hotel sales.)

Finally Hotels utilize several other alternative methods independent of RPM to optimize hotel sales:

- Lowering the product’s absolute price

- Increasing advertising and promotion, or making those efforts more effective

- Offering contractual promotion incentives (promotion allowances) to retailers

The above represents 18 examples of ways RPM could potentially be used to constrain trade, but none of these examples apply within the hotel industry. This compares with ZERO examples provided by the UK OFT of ways hotel RPM was anticompetitive. If the OFT legitimately has a case (despite the fact that they don’t feel they need one) it would be tremendously enlightening to understand its basis.

A Reality Check – Why Rate Parity is Beneficial to All Parties

Hotels need OTAs to augment their own wholly controlled distribution channels. Brand.com works fine for loyal frequent guests, but for the large audience of brand agnostic deal seekers, or travelers unfamiliar with a brand (or its presence in a given geographic market,) OTAs are a consumer-friendly, convenient alternative.

Las Vegas casinos were never been big fans of OTAs as distribution channels, but despite dominant market share, large group and convention blocks and legions of loyal players, and resources that are the envy of the rest of the hotel industry, they can not fill their rooms alone.

With 40,000+ and 23,000+ rooms respectively available for sale every night, even gaming powerhouses like MGM Resorts International and Caesar’s Entertainment, now have OTAs ranking among their largest tour operators.

Complicating the matter further, the casino groups must strike a managerial balance between strict corporate governance and property managerial autonomy when it comes to pricing strategies. Unpredictable demand swings create a tenuous equilibrium somewhere between a logical brand positioning-based pricing continuum and cannibalism of sister property volume and margin through pricing tactics to fill property distressed inventory gaps.

Despite the fact that a small OTA created this mess in the first place, RPM actually helps smaller players by leveling the playing field against the behemoth OTAs. With RPM in affect, start-ups and innovative small OTAs are able to sell rooms at the same price as the hotel brands and the OTAs as opposed to being disadvantaged by larger players that have negotiated higher agency commissions or deeper merchant discounts on net rates.

Without RPM, which also makes it much easier for hotels to manage pricing and inventory with hundreds or thousands of distribution relationships, hotels are more inclined to limit the number of wholesalers and retailers that they work with.

For those that believe this may not be the case, consider the airline industry, where the need for RPM was eliminated by instead eliminating travel agency commissions and dramatically reducing access to discounted wholesale fares. In a non-RPM environment, airlines can afford to be picky with their partners.

BookIt.com is a decently sized, second-tier OTA. When Delta Airlines elected to simplify its online distribution relationships, BookIt was cut off from access to selling Delta fares – completely. BookIt was not singled out, as that same round also cut off CheapOAir and OneTravel. A later round eliminated CheapAir, Vegas.com, AirGorilla, and Globester.

Those changes took place in December, 2010 and January, 2011. This was not mere posturing by Delta – to date, none of these relationships has been reestablished. ATL-MSP city-pair search results on these sites look a lot like a travelogue of connecting airports compared to the larger OTAs.

Plus, CheapOAir is not an insignificant player – they work with 450 air carriers, just not Delta. In August 2013, CheapOAir ranked higher than Travelocity, Hotwire and Orbitz and third behind Expedia and Priceline in US market share based on website visits.

Such reduced choice among distributors is not beneficial for consumers. With the high degree of fragmentation of hotels, the opportunity to exclude secondary distribution players is even greater within the hotel industry.

Ironically, partly due to RPM, Skoosh was able to start working with hotel groups before the contractual violations shut them down. Without RPM, it is unlikely many hotel groups would work with Skoosh based on its ability to generate incremental booking volume.

Now humorously, Skoosh is publicly ridiculing the OFT because the government didn’t eliminate RPM for all consumers. Being unable to gain competitive advantage by capitalizing on a large, well established frequent guest program, it seems Skoosh’s initial self-serving complaint, did not produce its desired outcome.

To a certain extent however, Skoosh is right. If the issue was seriously about addressing an unfair condition for consumers, why would consumers be forced to create a profile and purchase a hotel room through an OTA to gain access to a discount? Or what of under-privileged consumers that lack access to computers or a credit card typically required to guarantee a hotel room when booking online?

The commitments dictated by the OFT do nothing to to correct an inequity (since none really existed,) while creating new barriers for some to gain fair access to the best available rates. The OFT has now inadvertently disenfranchised certain travelers, undermined the legitimacy of best rate guarantees, and structurally created an indefensible downward pressure on hotel profitability. Not bad if you like your lose – lose – lose scenarios.

A World Without Hotel Rate Parity

If rate parity vanishes, all bets for the financial viability of the hotel industry are off. This could manifest itself in many ways. Like Delta, hotel groups could potentially cherry pick relationships with OTAs who would not be subject to rate parity.

If the OFT “solution” becomes the norm, I foresee OTAS using market power and cross-brand shopping capabilities to a) aggregate demand b) gain superior business intelligence, c) offer best rate guarantees that simply shave off a bit of margin d) usurp responsibility for defining hotel retail pricing from the hoteliers.

Since these discounts may be offered through a discounted price or commission rebates, integrated wholesaler/retailers like OTAs have an extensive arsenal of pricing weapons to play with.

Lacking resale price maintenance, a hotel loses its ability to properly manage its retail pricing structure. This is particularly problematic for perishable services like hotel rooms where unsold inventory immediately loses its value once a specific date passes.

Hotel inventory is now largely priced dynamically and travel seller compensation is generally based on a fixed commission percentage (agency model) or a net wholesale rate that is discounted by a specific percentage from the best available retail price. Most often, the only absolute price that is set is the BAR that serves as the basis for the other prices.

On a retail basis, it becomes impossible for a hotel to match a travel seller’s discounted/rebated price. Even if the hotel reduces its price to match, the competitor possesses a mechanism to match or undercut any rate the hotel may offer a prospective guest – to the point the hotel offers a rate that is equal to the net (or net-of-commission) rate provided to the travel seller.

The greatest factor however, potentially impacts existing customers of the travel sellers or hotels. First, travel sellers gain a second structural advantage – by definition, they sell product across multiple product categories and hotel brands. Any previous airline booking, hotel stay, car rental, etc. regardless of the travel supplier’s geographic area or brand creates a pre-existing customer relationship and eligibility to access hotel rates below market pricing.

Even the largest hotel groups can only establish a customer relationship if a traveler makes a purchase from their specific brand. The order of magnitude is staggering. Booking.com has a portfolio of 300,000 hotels alone. But this is dwarfed by the aggregation of customers across parent Priceline’s portfolio of product that includes Priceline, Kayak and RentalCars.com. TripAdvisor’s meta-search product selling 500,000+ properties and registered relationships with millions of reviewers takes the notion of a customer to a new level. Apple, with the world’s largest database of user credit card numbers, or Google, across all of its registered product relationships dwarf the hotel brands, not to mention the single unit, independent hotelier.

The daunting competitive scope however may have less bearing than the most damaging impact – hotel guest profitability.

Hotel frequent guest programs, largely driven by corporate bookings, represent the most valuable guest segment for the hotel. Relatively brand loyal, these individuals sport both the greatest repeat stay frequency (which lowers marketing costs) and the highest average daily rates, since like airlines, business travelers tend to see higher pricing than those traveling on leisure trips.

With all research indicating that price reductions do not drive incremental demand creation, hotels face the reality that discounting only serves as an effective method to shift share from competitors.

Having been involved with negotiating hundreds, if not thousands of hotel deals (from both sides of the table) throughout my career, I can safely say that if a group can demonstrate scale, pricing power and a high degree of customer engagement, those benefits will be leveraged during negotiations. While rate parity protections may be stricken by new resale price maintenance rules, the ability for OTAs to negotiate most-favored nations pricing concessions – either on a net rate, discount percentage or commission basis – are not.

Hotels may be forced into deciding between two undesirable options – a) discontinuing relationships with distribution partners (resulting in a share loss to competitors) or b) forfeiting control of their retail pricing structures to intermediaries.

Hotels attempting to mirror OTA discounts directed at frequent guests would be structurally discounting business sourced from their least price sensitive and brand loyal market segment – a cannibalistic marketing strategy that would nearly guarantee lower profitability.

Unlike the airline industry that eliminated travel agency commissions and dramatically reduced access to wholesale pricing, the high degree of fragmentation within the hotel industry will not result in an industry-wide adoption of a more stringent business model. As a matter of fact, if hotels attempted that course, the intermediaries would immediately cry foul and head to court with accusations of restraint of trade.

For hotels, the dilemma is worse than being stuck between a rock and a hard place. It is more like being stuck between a rolling boulder and an abyss. Fundamental changes resulting from the UK OFT case, and its expansion to cover the EU, will affect the global hotel business and create a new normal that cannot be easily undone through business practice or legal appeal.

When UK consumers who are registered with OTAs start getting access to across-the-board discounts on hotels in the EU, the genie will be out of the bottle. As these are private sales, OTAS will be eager to extend the practice beyond UK citizens and EU hotels.

As few incentives will exist to confirm UK citizenship/residency the creation of sockpuppet accounts will be rampant, perhaps with a cottage industry arising as affiliates learn how to cleverly facilitate access to the reduced pricing. This could get very ugly – very fast.

Clearly, the merchant and agency models will not disappear. Hotels will continue to work with OTAs, but the OTAs will be able to attract and retain consumers with financial incentives to grow market share. The only question will be how much share do they gain and how quickly can the hotels reestablish equilibrium to the distribution equation.

Hopefully the David v. Goliath relationships between European hotels and OTAs will not devolve into a global Bambi v. Godzilla match-up.

Hotel industry leadership globally – not just in Europe – needs to begin contingency planning for this eventuality now – procrastinating will only bring greater earnings losses and increased market share deficits. the demise of rate parity / resale price maintenance policies may represent the single greatest strategic challenge facing hoteliers in the decade ahead.